10 of the Best Poems of Czeslaw Milosz

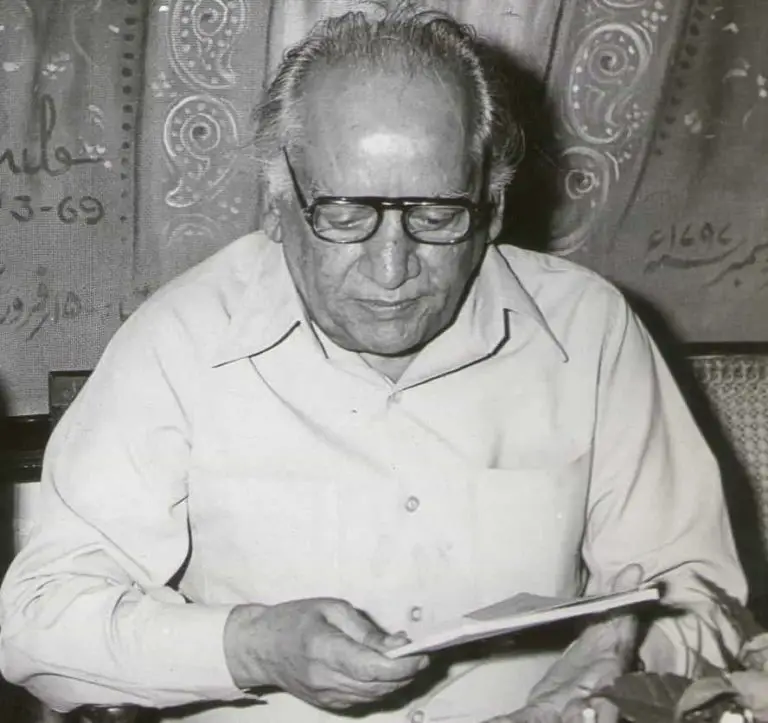

Czeslaw Milosz was a Polish-American poet and writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. Milosz won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1980. According to Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky, Milosz was perhaps the greatest poet of the 20th century. The recurrent themes of Milosz’s poetry are morality, history, and faith. Throughout his lifetime, he produced a number of poetic works in Polish. Here you can find 10 of the most famous poems written by Czeslaw Milosz.

A Song on the End of the World

“A Song on the End of the World” is one of the best-known poems of Czeslaw Milosz. It was published in his poetry collection Ocalenie (“Rescue”), written just after the end of the Second World War. Milosz wrote this poem in Warsaw during the Nazi occupation in 1944.

In this poem, Milosz optimistically declares there won’t be any end of the world as long as the beautiful things of nature are kept intact. Those who thought the world would end after the Great Wars, the poet answers them in these lines of the poem.

And those who expected lightning and thunder

Are disappointed.

And those who expected signs and archangels’ trumps

Do not believe it is happening now.

As long as the sun and the moon are above,

As long as the bumblebee visits a rose,

As long as rosy infants are born

No one believes it is happening now.

Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he’s much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

There will be no other end of the world,

There will be no other end of the world.

Source: A Song on the End of the World

Campo dei Fiori

It is another of the best-known poems that Milosz wrote while he was in Warsaw in 1943. This piece also appears in Ocalenie (1945). In this poem, Milosz talks about people’s indifference to others’ deaths. According to Milosz, the central theme of this poem is the vulnerability and loneliness of dying men. It was written as a sort of moral obligation that made the poet write this piece. Here are a few crucial lines from the poem:

On this same square

they burned Giordano Bruno.

Henchmen kindled the pyre

close-pressed by the mob.

Before the flames had died

the taverns were full again,

baskets of olives and lemons

again on the vendors’ shoulders.

(…)

Those dying here, the lonely

forgotten by the world,

our tongue becomes for them

the language of an ancient planet.

Until, when all is legend

and many years have passed,

on a new Campo dei Fiori

rage will kindle at a poet’s word.

Source: Campo dei Fiori

A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto

It was one of the poems that were selected by the Nobel Library of the Swedish Academy to feature in their list of Czeslaw Milosz’s best poetry. This piece belongs to the poetry cycle published in Ocalenie, “The Voices of Poor People”. Milosz wrote this poem in Warsaw in 1943. In this poem, he describes the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto. Being a jew, the speaker feels sad as he managed to survive the brutalities while others could not.

I am afraid, so afraid of the guardian mole.

He has swollen eyelids, like a Patriarch

Who has sat much in the light of candles

Reading the great book of the species.

What will I tell him, I, a Jew of the New Testament,

Waiting two thousand years for the second coming of Jesus?

My broken body will deliver me to his sight

And he will count me among the helpers of death:

The uncircumcised.

Source: A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto

Incantation

This poem was translated by Robert Pinsky and Czeslaw Milosz. It was written in 1968. In this poem, Milosz talks about human reason. He posits the good side of human reason over the bad one in order to convey his support for the former. In the last few lines, the poet explores how new poetry and philosophical ideas are going to redeem humankind from the harshness of past events. Here are a few lines from the poem:

Human reason is beautiful and invincible.

No bars, no barbed wire, no pulping of books,

No sentence of banishment can prevail against it.

It establishes the universal ideas in language,

And guides our hand so we write Truth and Justice

With capital letters, lie and oppression with small.

(…)

Beautiful and very young are Philo-Sophia

And poetry, her ally in the service of the good.

As late as yesterday Nature celebrated their birth,

The news was brought to the mountains by a unicorn and an echo.

Their friendship will be glorious, their time has no limit.

Their enemies have delivered themselves to destruction.

Source: Incantation

Ars Poetica?

“Ars Poetica?” is one of the best-known poems of Czeslaw Milosz. The question mark attached to the title gives a hint to readers regarding the subject matter of the poem. Here, Milosz asks about the nature of poetry, whether it is governed by demons or angels. Let’s explore a few lines from the poem:

I have always aspired to a more spacious form

that would be free from the claims of poetry or prose

and would let us understand each other without exposing

the author or reader to sublime agonies.

(…)

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

What I’m saying here is not, I agree, poetry,

as poems should be written rarely and reluctantly,

under unbearable duress and only with the hope

that good spirits, not evil ones, choose us for their instrument.

Source: Ars Poetica?

Encounter

This ironic poem was written in 1936 at Wilno. It is perhaps one of the shortest yet probing poems that Milosz ever wrote. In this piece, the poet does not feel sad about the loss. Rather he wonders why such things ever took place. He evaluates the actual outcome of the event, a hint at the World War. Let’s have a look at the text.

We were riding through frozen fields in a wagon at dawn.

A red wing rose in the darkness.

And suddenly a hare ran across the road.

One of us pointed to it with his hand.

That was long ago. Today neither of them is alive,

Not the hare, nor the man who made the gesture.

O my love, where are they, where are they going

The flash of a hand, streak of movement, rustle of pebbles.

I ask not out of sorrow, but in wonder.

Source: Encounter

Dedication

“Dedication” is one of the Ocalenie poems that Milosz wrote while he was in Warsaw. This piece, translated into English by the poet himself, was written in 1945. It is indeed one of the best-loved poems of Milosz. In this poem, Milosz dedicates his book of poetry to the dead. He does so in order to make their souls never return to the living humankind.

What is poetry which does not save

Nations or people?

A connivance with official lies,

A song of drunkards whose throats will be cut in a moment,

Readings for sophomore girls.

That I wanted good poetry without knowing it,

That I discovered, late, its salutary aim,

In this and only this I find salvation.

They used to pour millet on graves or poppy seeds

To feed the dead who would come disguised as birds.

I put this book here for you, who once lived

So that you should visit us no more.

Source: Dedication

Love

What does love mean? It differs from person to person. For Milosz,

Love means to learn to look at yourself

The way one looks at distant things

For you are only one thing among many.

And whoever sees that way heals his heart,

Without knowing it, from various ills—

Source: Love

It means the poet advises readers to distance themselves from selfishness. They must look at themselves as faraway objects. In this way, they can be aloof at their hearts from various ills of the modern world.

Study of Loneliness

“Study of Loneliness” is among Milosz’s best-known poems. In this poem, the poet presents a speaker who roams alone in a desert. The colors of the landscape reminded him of the vibrance of humanity. He felt happy at the same time, sad as none was going to save him from this desert of loneliness. Let’s have a look at the few lines from the poem.

A guardian of long-distance conduits in the desert?

A one-man crew of a fortress in the sand?

Whoever he was. At dawn he saw furrowed mountains

The color of ashes, above the melting darkness,

Saturated with violet, breaking into fluid rouge,

Till they stood, immense, in the orange light.

Day after day. And, before he noticed, year after year.

For whom, he thought, that splendor? For me alone?

Source: Study of Loneliness

You Who Wronged

The lines from “You Who Wronged” are inscribed on the Monument of the Fallen Shipyard Workers of 1970 in Gdansk. Milosz’s poem inspired the anti-communist Solidarity movement in the early 1980s in Poland. This poem was written in 1950 when Milosz was in Washington D.C.

This poem is written protest of the murder of a simple man by hanging him from a tree. The poet warns the tormentor that he can kill him for going against them. But, there will be another poet to speak up against injustice. Let’s explore some lines from the text.

You who wronged a simple man

Bursting into laughter at the crime,

And kept a pack of fools around you

To mix good and evil, to blur the line,

(…)

Do not feel safe. The poet remembers.

You can kill one, but another is born.

The words are written down, the deed, the date.

And you’d have done better with a winter dawn,

A rope, and a branch bowed beneath your weight.

Source: You Who Wronged

FAQs

The Polish-American poet Czeslaw Milosz wrote about morality, politics, history, and faith. His famous poems encompass the events of World War II.

“A Song on the End of the World” is perhaps Czeslaw Milosz’s best-known poem alongside “A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto” and “Campo dei Fiori”.

External Resources

- Check out A Book Of Luminous Things by Czeslaw Milosz (1998) — This collection includes Milosz’s personal selection of poems. It’s a testament to the stunning varieties of human experience that can be shared in words and images.

- Biography of Czeslaw Milosz — Read about the biography of the poet.

- About Czeslaw Milosz — Learn more about the poet’s life and his works.

- Poet Profile & Poems of Czeslaw Milosz — Explore the poet’s profile and read more of his poems.

- Nobel Lecture of Czeslaw Milosz — Read the full lecture delivered at the Nobel Award ceremony.