10 of the Best Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay is one of the most important American poets of the 20th century and was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923 after the formal establishment of the award. Millay composed her first poem, “Renascence,” in 1912 for a poetry contest at the age of 20. Though the poem was considered the best submission, it failed to grab the top three spots in the contest. But, this piece launched her career as a poet.

In November 1912, poet Arthur Davison Ficke wrote a letter to Millay concerning her poem “Renascence.” He expressed his flattering doubts by saying:

No sweet young thing of twenty ever ended the poem with this one ends. It takes a brawny male of forty-five to do that.

In her reply, Millay sent one of her enticing photographs and teasingly said:

Brawny male? I cling to my femininity and gentleman when a woman insists that she is twenty, you must not call her forty-five. That is more than wicked. It is indiscreet.

P.S. The brawny male sents his picture.

After graduating from Vassar College in 1917, Millay went to New York City and published her first book of poetry, Renascence, and Other Poems. She went on to produce some of her most important works, including the poetry collections, A Few Figs From Thistles (1920) and The Harp-Weaver, and Other Poems (1923). “The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver” was one of her poems that was selected for the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923.

On this list, we are going to present 10 of the most famous poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay. What are you waiting for? Let’s dive into the list of Millay’s best poems.

Renascence

“Renascence” is one of the finest poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay. She wrote this piece in 1912 for a poetry contest. It won fourth place. This led to a controversy that somehow brought Millay to fame and wide recognition. So, writing this poem was a turning point in her career.

This lyric explores the relationship of a speaker to humanity as well as nature. The speaker narrates the scene from the top of a mountain. Being overwhelmed by nature, she thinks of human suffering and death. In simple words, nature’s calm and serene beauty brought about the “renascence” in the speaker’s heart. Here are some memorable lines from the poem:

All I could see from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood;

I turned and looked another way,

And saw three islands in a bay.

So with my eyes I traced the line

Of the horizon, thin and fine,

Straight around till I was come

Back to where I’d started from;

And all I saw from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood.

Over these things I could not see;

These were the things that bounded me;

And I could touch them with my hand,

Almost, I thought, from where I stand.

And all at once things seemed so small

My breath came short, and scarce at all.

But, sure, the sky is big, I said;

Miles and miles above my head;

So here upon my back I’ll lie

And look my fill into the sky.

And so I looked, and, after all,

The sky was not so very tall.

The sky, I said, must somewhere stop,

And—sure enough!—I see the top!

The sky, I thought, is not so grand;

I ‘most could touch it with my hand!

And reaching up my hand to try,

I screamed to feel it touch the sky.

The world stands out on either side

No wider than the heart is wide;

Above the world is stretched the sky,—

No higher than the soul is high.

The heart can push the sea and land

Farther away on either hand;

The soul can split the sky in two,

And let the face of God shine through.

But East and West will pinch the heart

That can not keep them pushed apart;

And he whose soul is flat—the sky

Will cave in on him by and by.

Source: Renascence

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why

“What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why” is one of the best-known sonnets by Millay. This piece is about aging and one speaker’s longing for her youthful days. Once she was admired and loved by several men. As she grew older, her life turned into a tree, standing alone in the winter landscape. The birds of love no more sing the heartwarming songs.

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning; but the rain

Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply,

And in my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Thus in the winter stands the lonely tree,

Nor knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone,

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver

Millay won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for the collection The Harp-Weaver, and Other Poems in 1923. “The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver” was published in this collection and it is one of her best-known poems. This ballad is about a poor woman and her son. She laments for her child as she cannot provide a suitable dress for him. As the winter approaches, she grows sadder. Then comes the turning point in the poem.

She weaves not only regal clothes for her son but sings some melodious songs by playing the harp with a woman’s head. At the end of the poem, the mother dies. But, she leaves the clothes of a king’s son behind for her beloved son. Read the heart-wrenching story of the mother and son:

“Son,” said my mother,

When I was knee-high,

“You’ve need of clothes to cover you,

And not a rag have I.

“There’s nothing in the house

To make a boy breeches,

Nor shears to cut a cloth with

Nor thread to take stitches.

“There’s nothing in the house

But a loaf-end of rye,

And a harp with a woman’s head

Nobody will buy,”

And she began to cry.

That was in the early fall.

When came the late fall,

“Son,” she said, “the sight of you

Makes your mother’s blood crawl,—

“Little skinny shoulder-blades

Sticking through your clothes!

And where you’ll get a jacket from

God above knows.

“It’s lucky for me, lad,

Your daddy’s in the ground,

And can’t see the way I let

His son go around!”

And she made a queer sound.

That was in the late fall.

When the winter came,

I’d not a pair of breeches

Nor a shirt to my name.

I couldn’t go to school,

Or out of doors to play.

And all the other little boys

Passed our way.

“Son,” said my mother,

“Come, climb into my lap,

And I’ll chafe your little bones

While you take a nap.”

And, oh, but we were silly

For half an hour or more,

Me with my long legs

Dragging on the floor,

A-rock-rock-rocking

To a mother-goose rhyme!

Oh, but we were happy

For half an hour’s time!

But there was I, a great boy,

And what would folks say

To hear my mother singing me

To sleep all day,

In such a daft way?

Men say the winter

Was bad that year;

Fuel was scarce,

And food was dear.

A wind with a wolf’s head

Howled about our door,

And we burned up the chairs

And sat on the floor.

All that was left us

Was a chair we couldn’t break,

And the harp with a woman’s head

Nobody would take,

For song or pity’s sake.

The night before Christmas

I cried with the cold,

I cried myself to sleep

Like a two-year-old.

And in the deep night

I felt my mother rise,

And stare down upon me

With love in her eyes.

I saw my mother sitting

On the one good chair,

A light falling on her

From I couldn’t tell where,

Looking nineteen,

And not a day older,

And the harp with a woman’s head

Leaned against her shoulder.

Her thin fingers, moving

In the thin, tall strings,

Were weav-weav-weaving

Wonderful things.

Many bright threads,

From where I couldn’t see,

Were running through the harp-strings

Rapidly,

And gold threads whistling

Through my mother’s hand.

I saw the web grow,

And the pattern expand.

She wove a child’s jacket,

And when it was done

She laid it on the floor

And wove another one.

She wove a red cloak

So regal to see,

“She’s made it for a king’s son,”

I said, “and not for me.”

But I knew it was for me.

She wove a pair of breeches

Quicker than that!

She wove a pair of boots

And a little cocked hat.

She wove a pair of mittens,

She wove a little blouse,

She wove all night

In the still, cold house.

She sang as she worked,

And the harp-strings spoke;

Her voice never faltered,

And the thread never broke.

And when I awoke,—

There sat my mother

With the harp against her shoulder

Looking nineteen

And not a day older,

A smile about her lips,

And a light about her head,

And her hands in the harp-strings

Frozen dead.

And piled up beside her

And toppling to the skies,

Were the clothes of a king’s son,

Just my size.

Love Is Not All

“Love Is Not All” is one of the best-known sonnets of Millay that speaks of a speaker’s dejection in love. This poem is written in the form of a Shakespearean sonnet. Here, Millay describes how a heartbroken speaker feels as she does in her first free-verse poem, “Spring“. For her, love is not everything. Yet she cannot even trade love for something better.

Listen to Millay reading “Love Is Not All” and read the sonnet below:

Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

And rise and sink and rise and sink again;

Love can not fill the thickened lung with breath,

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

Even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution’s power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would.

Conscientious Objector

A conscientious objector is one who has refused to go to war for the sake of freedom of conscience. In this poem, Millay applies the term to a horse that does not inform the rider of the upcoming dangers. It knows death is inevitable. This poem is best known for its portrayal of “Death” and Millay’s straightforward refusal to give in. Explore the in-depth analysis of “Conscientious Objector” and read the poem below:

I shall die, but

that is all that I shall do for Death.

I hear him leading his horse out of the stall;

I hear the clatter on the barn-floor.

He is in haste; he has business in Cuba,

business in the Balkans, many calls to make this morning.

But I will not hold the bridle

while he clinches the girth.

And he may mount by himself:

I will not give him a leg up.

Though he flick my shoulders with his whip,

I will not tell him which way the fox ran.

With his hoof on my breast, I will not tell him where

the black boy hides in the swamp.

I shall die, but that is all that I shall do for Death;

I am not on his pay-roll.

I will not tell him the whereabout of my friends

nor of my enemies either.

Though he promise me much,

I will not map him the route to any man’s door.

Am I a spy in the land of the living,

that I should deliver men to Death?

Brother, the password and the plans of our city

are safe with me; never through me

Shall you be overcome.

I, Being born a Woman and Distressed

“I, being born a woman and distressed” is one of the most famous poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay. It appears in The Harp-Weaver, and Other Poems (1923). This piece imitates the Italian sonnet form. In this poem, Millay presents a speaker who craves intimacy with her partner. She knows that sometimes it is better not to hear the calling of her “stout blood.” The mental scorn originating from her bodily frenzy makes this speaker sad and distressed. Let’s read this emotionally charged sonnet below:

I, being born a woman and distressed

By all the needs and notions of my kind,

Am urged by your propinquity to find

Your person fair, and feel a certain zest

To bear your body’s weight upon my breast:

So subtly is the fume of life designed,

To clarify the pulse and cloud the mind,

And leave me once again undone, possessed.

Think not for this, however, the poor treason

Of my stout blood against my staggering brain,

I shall remember you with love, or season

My scorn with pity,—let me make it plain:

I find this frenzy insufficient reason

For conversation when we meet again.

First Fig

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

This short, four-line poem appears in Millay’s 1920 poetry collection A Few Figs From Thistles. The book drew controversy for presenting the theme of female sexuality openly. It is filled with Millay’s feministic views. “First Fig” is a fragment of a speaker’s feminine desires. The brevity of the poem keeps the doors of interpretations always open.

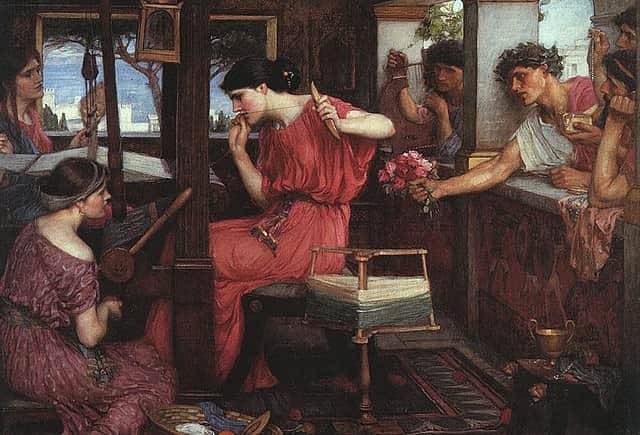

An Ancient Gesture

I thought, as I wiped my eyes on the corner of my apron:

Penelope did this too.

And more than once: you can’t keep weaving all day

And undoing it all through the night;

Your arms get tired, and the back of your neck gets tight;

And along towards morning, when you think it will never be light,

And your husband has been gone, and you don’t know where, for years.

Suddenly you burst into tears;

There is simply nothing else to do.

And I thought, as I wiped my eyes on the corner of my apron:

This is an ancient gesture, authentic, antique,

In the very best tradition, classic, Greek;

Ulysses did this too.

But only as a gesture,—a gesture which implied

To the assembled throng that he was much too moved to speak.

He learned it from Penelope…

Penelope, who really cried.

Millay’s “An Ancient Gesture” delves into a mythological gesture that speaks for the mental state of the speaker. She is sad but cannot reveal her true feelings. It is customary to hide feminine emotions aside. As Millay says, this gesture is “ancient,” “authentic,” and “unique.” She thinks Penelope might be the first woman to start this custom and later Ulysses (men) also adopted it, keeping the emotional aspect aside.

Time does not bring relief; you all have lied

As the title hints at, the sonnet “Time does not bring relief; you all have lied” is about a speaker’s disgust over the fact that every scar of the past heals with time. She rejects this idea as she talks about her heartbreak. No matter wherever she goes or whatever she does to forget her lover, she utterly fails. The old thoughts keep coming, making her sadder than before.

Time does not bring relief; you all have lied

Who told me time would ease me of my pain!

I miss him in the weeping of the rain;

I want him at the shrinking of the tide;

The old snows melt from every mountain-side,

And last year’s leaves are smoke in every lane;

But last year’s bitter loving must remain

Heaped on my heart, and my old thoughts abide.

…

There are a hundred places where I fear

To go,—so with his memory they brim.

And entering with relief some quiet place

Where never fell his foot or shone his face

I say, “There is no memory of him here!”

And so stand stricken, so remembering him.

Apostrophe to Man

This poem is addressed to humankind who was preparing for another war after the end of the First World War. In this piece, Millay expresses her disgust over the way everything starts to deteriorate. She strongly detests the actions that kill the very essence of humanity. It is one of her well-known poems. Let’s read the poem below:

(On reflecting that the world

is ready to go to war again)

…

Detestable race, continue to expunge yourself, die out.

Breed faster, crowd, encroach, sing hymns, build

bombing airplanes;

Make speeches, unveil statues, issue bonds, parade;

Convert again into explosives the bewildered ammonia

and the distracted cellulose;

Convert again into putrescent matter drawing flies

The hopeful bodies of the young; exhort,

Pray, pull long faces, be earnest,

be all but overcome, be photographed;

Confer, perfect your formulae, commercialize

Bacteria harmful to human tissue,

Put death on the market;

Breed, crowd, encroach,

expand, expunge yourself, die out,

Homo called sapiens.

You’ve finished reading all the best Edna St. Vincent Millay poems. Apart from the poems mentioned here, some other famous poems of Millay include:

- “Euclid alone has looked on Beauty bare”

- “Penitent”

- “Dirge Without Music”

- “Second Fig”

- “Recuerdo”

- “Bluebeard”

You can explore the most famous poems by other poets as well.

FAQs

“Renascence” is one of the most famous poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay that she wrote in 1912 for a poetry competition. Though it did not make it to the top three, this poem boosted her writing career greatly.

Millay is best known for her sonnets, including “What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,” “Love Is Not All,” and “Time does not bring relief.” Some of Millay’s popular lyric poems are “The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver,” “Conscientious Objector,” “An Ancient Gesture,” and “Spring.”

Useful Resources

- Check out Collected Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay — This posthumous collection (1956) of Millay includes her memorable poems, personal letters, and some of her never-seen-before photos.

- About Edna St. Vincent Millay — Read about the poet’s life and her poems.

- Poet Profile & Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay — Learn more about the poet and read more of her poems.

- Millay’s Poetry Recordings — Listen to Millay’s powerful voice and immerse yourself in her poetic world.