10 of the Best Anna Akhmatova Poems

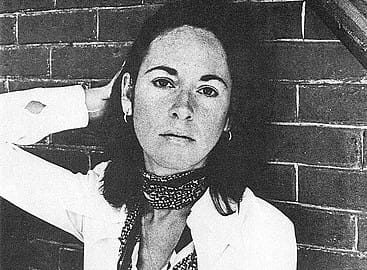

One of the influential modern poets, Anna Akhmatova lived during the tumultuous phases of world history in Soviet Russia. Akhmatova, a touchstone and anachronism, was the voice of the long-suppressed 20th-century women. While fighting her lifelong battle with the mighty pen, she tried not to yield to terror, authority, and might. Akhmatova is not just a name, but a literary trademark like Emily Dickinson or Edna St. Vincent Millay was in American literature. “The keening muse” of poet Joseph Brodsky, Akhmatavo not only earned the title, “Soul of the Silver Age,” but was also condemned as “half harlot, half nun.”

Akhmatova started writing poetry at the age of eleven and her career took off with the publication of her first poem, “On his husband you may see many glittering rings,” at the age of seventeen. Her debut collection, Evening, was published in 1912 by the Guild of Poets. The collection was an instant hit and she went on to publish her second book, Rosary, two years after the publication of her first collection.

Post-1925, her prolific career graph took a major downturn due to the strict censorship and suppression by the Stalinist government. Irrespective of the dark period in her career, she remained and will remain one of the important literary figures. Her poetry familiarizes us with her experience of living during the darkest hours of human history. Here you can find some of the most famous poems by Anna Akhmatova, which showcase her versatility and merit as a poet.

Poem Without a Hero

Poema bez geroia, translated as Poem Without a Hero is the longest and perhaps, best-known work of Anna Akhmatova. Composed between 1940 and 1965, Akhmatova went on to write and rewrite this poem throughout her literary career. It is regarded as one of the influential works of 20th-century world literature. Some of the important themes in this long narrative piece include memories, atonement, and lamentation for the past.

Read some memorable lines from Akhmatova’s masterpiece, Poem Without a Hero, translated by Stanley Kunitz and Max Hayward:

I have lit my treasured candles,

one by one, to hallow this night.

With you, who do not come,

I wait the birth of the year.

Dear God!

the flame has drowned in crystal,

and the wine, like poison, burns

Old malice bites the air,

old ravings rave again,

though the hour has not yet struck.

…

In the black sky no star is seen,

somewhere in ambush lurks the Angel of Death,

but the spices tongues of the masqueraders

are loose and shameless

A shout:

“Make way for the hero!”

Ah yes. Displacing the tall one,

he will step forth now without fail

and sing to us about holy vengeance…

– from Poems of Akhmatova (1973)

Requiem

Requiem (originally, Rekviem) is another best-known poem by Anna Akhmatova. This elegiac cycle of poems chronicles the Stalinist terror, also known as the Great Purge of ‘37. Composed between 1935 and 1940, this piece was not published in Russia during Akhmatova’s lifetime due to its direct references to the Stalinist oppression. It begins with a prose paragraph recounting the event of standing outside of the Leningrad Prison to see Lev, Akhmatova’s only son, who was captured just because he was the son of Nikolay Gumilev.

INSTEAD OF A PREFACE

During the frightening years of the Yezhov terror, I spent seventeen months waiting in prison queues in Leningrad. One day, somehow, someone ‘picked me out’. On that occasion there was a woman standing behind me, her lips blue with cold, who, of course, had never in her life heard my name. Jolted out of the torpor characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear (everyone whispered there) – ‘Could one ever describe this?’ And I answered – ‘I can.’ It was then that something like a smile slid across what had previously been just a face.

[The 1st of April in the year 1957. Leningrad]

In the “Dedication” of Requiem, Akhmatova writes:

Mountains fall before this grief,

A mighty river stops its flow,

But prison doors stay firmly bolted

Shutting off the convict burrows

And an anguish close to death.

Fresh winds softly blow for someone,

Gentle sunsets warm them through; we don’t know this,

We are everywhere the same, listening

To the scrape and turn of hateful keys

And the heavy tread of marching soldiers.

…

As if a beating heart is painfully ripped out, or,

Thumped, she lies there brutally laid out,

But she still manages to walk, hesitantly, alone.

Where are you, my unwilling friends,

Captives of my two satanic years?

What miracle do you see in a Siberian blizzard?

What shimmering mirage around the circle of the moon?

I send each one of you my salutation, and farewell.

Explore the full text of Requiem.

On his hand you may see many glittering rings…

“On his hand you may see many glittering rings” is the first and only poem that she signed with her real name, Anna Gorenko. All the rest of her poems were written under her pen name Anna Akhmatova. She composed the poem at the age of seventeen. It was published in her would-be husband Gumilev’s journal, Sirius in 1907.

Read the full poem below:

On his hand you may see many glittering rings,

Those are tender girls’ hearts, rightful trophies of flings.

…

There a diamond exults and an opal daydreams,

And a beautiful ruby emits crimson whims.

…

But on his pallid hand my gemstone will not shine,

None shall ever be granted this jewel of mine.

…

In my dream a gold ray of the moon forged this ring

As it slipped on my finger it whispered to me:

…

“Safeguard my precious gift; treat your fancy with pride!”

I will not fail my ring. There’ll be none to confide.

You Will Hear Thunder

“You Will Hear Thunder” is one of the most famous poems by Akhmatova. It was one of the earliest poems written during the Silver Age. In this poem, the speaker addresses her beloved and describes how he is going to miss her when she is no longer alive.

Read these bittersweet lines from the poem:

You will hear thunder and remember me,

And think: she wanted storms. The rim

Of the sky will be the colour of hard crimson,

And your heart, as it was then, will be on fire.

…

That day in Moscow, it will all come true,

when, for the last time, I take my leave,

And hasten to the heights that I have longed for,

Leaving my shadow still to be with you.

Everything

“Everything” is a poem about the death and destruction that occurred during the Great Terror and the two World Wars. The crux of the poem is that after the bleakest night, comes the dawn of tomorrow flickering with frail beams of hope.

Everything’s looted, betrayed and traded,

black death’s wing’s overhead.

Everything’s eaten by hunger, unsated,

so why does a light shine ahead?

…

By day, a mysterious wood, near the town,

breathes out cherry, a cherry perfume.

By night, on July’s sky, deep, and transparent,

new constellations are thrown.

…

And something miraculous will come

close to the darkness and ruin,

something no-one, no-one, has known,

though we’ve longed for it since we were children.

Lot’s Wife

First composed in Russian in 1924, Akhmatova’s “Lot’s Wife” is one of her best-loved poems. It was translated by Stanley Kunitz and Max Hayward, and published in the 1973 collection Poems of Akhmatova. This poem alludes to the Genesis story of Lot’s wife, who upon looking back at her beloved city, Sodom, was turned into a pillar of salt. Akhmatova sympathizes with her tragic story and grieves for the outcome in her poem, which reads:

And the just man trailed God’s shining agent,

over a black mountain, in his giant track,

while a restless voice kept harrying his woman:

“It’s not too late, you can still look back

…

at the red towers of your native Sodom,

the square where once you sang, the spinning-shed,

at the empty windows set in the tall house

where sons and daughters blessed your marriage-bed.”

…

A single glance: a sudden dart of pain

stitching her eyes before she made a sound . . .

Her body flaked into transparent salt,

and her swift legs rooted to the ground.

…

Who will grieve for this woman? Does she not seem

too insignificant for our concern?

Yet in my heart I never will deny her,

who suffered death because she chose to turn.

I Wrung My Hands

“I Wrung My Hands” is one of her earlier and best-known poems. She wrote this poem while she was in Kiev in 1911. The translated version of the poem could be found in the most popular collection of Akhmatova’s poetry, Poems of Akhmatova. This poem is composed of four quatrains with the ABCB rhyme scheme. It is about a speaker who has made her loved one “drunk with an astringent sadness.” She apologizes for her recklessness while her cold lover walks away:

I’ll never forget. He went out, reeling;

his mouth was twisted, desolate. . .

I ran downstairs, not touching the banisters,

and followed him as far as the gate.

…

And shouted, choking: “I meant it all

in fun. Don’t leave me, or I’ll die of pain.”

He smiled at me — oh so calmly, terribly —

and said: “Why don’t you get out of the rain?”

Grey-Eyed King

One of the most popular poems of Anna Akhmatova, “Grey-Eyed King” was written in 1910 and published in her first poetry collection Evening or Vecher in 1912. She carefully selected the poems published in the book and chose only 35 poems over the other 200 poems that she wrote by 1911. With the publication of this collection, Akhmatova became instantly popular in the Russian literary circle. This piece, consisting of seven rhyming couplets, mourns the death of a young king.

Read the elegiac poem, translated by Yevgeny Bonver below:

Hail! Hail to thee, o, immovable pain!

The young grey-eyed king had been yesterday slain.

…

This autumnal evening was stuffy and red.

My husband, returning, had quietly said,

…

“He’d left for his hunting; they carried him home;

They’d found him under the old oak’s dome.

…

I pity the queen. He, so young, past away!…

During one night her black hair turned to grey.”

He found his pipe on a warm fire-place,

And quietly left for his usual race.

…

Now my daughter will wake up and rise —

Mother will look in her dear grey eyes…

…

And poplars by windows rustle as sing,

“Never again will you see your young king…”

Crucifix

The short poem “Crucifix” alludes to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. This piece features Akhmatova’s precise choice of expression and words. It summarizes the tale of Christ’s crucifixion within nine lines with particular emphasis on a mother’s pain upon seeing her child lying coldly in a grave.

Do not cry for me, Mother, seeing me in the grave.

…

I

This greatest hour was hallowed and thandered

By angel’s choirs; fire melted sky.

He asked his Father: “Why am I abandoned…?”

And told his Mother: “Mother, do not cry…”

…

II

Magdalena struggled, cried and moaned.

Peter sank into the stone trance…

Only there, where Mother stood alone,

None has dared cast a single glance.

I Taught Myself to Live Simply

“I Taught Myself to Live Simply” is also known as “I’ve learned to live simply, wisely.” It was first published in 1913 and included in her second collection of poetry, Rosary (1914). The poem begins with the speaker describing how she lives in contemplation of nature and praying to God:

I taught myself to live simply and wisely,

to look at the sky and pray to God,

and to wander long before evening

to tire my superfluous worries.

In the following lines, she describes how she composes poetry tapping on the pacifying energy surrounding her. She remains so invested in her thoughts that she cannot even hear who knocks at her mind’s door.

When the burdocks rustle in the ravine

and the yellow-red rowanberry cluster droops

I compose happy verses

about life’s decay, decay and beauty.

I come back. The fluffy cat

licks my palm, purrs so sweetly

and the fire flares bright

on the saw-mill turret by the lake.

Only the cry of a stork landing on the roof

occasionally breaks the silence.

If you knock on my door

I may not even hear.

FAQs

Poem Without a Hero, the longest poem by Anna Akhmatova, is regarded as her best-known and the most famous work. She started writing this poem in 1940 and finished it by 1965. It was dedicated to the memory of those who passed away during the Siege of Leningrad. Akhmatova is best-remembered for this narrative poem along with her lyrical cycle of verse, Requiem.

In her early career, Akhmatova mainly wrote sentiment romantic verses. By the end of her life, she fixated on the bleak and serious themes. Throughout her career, she experimented with different poetic forms.

Useful Resources

- Check Out Poems of Akhmatova — This influential book of Akhmatova’s verse, translated by Stanley Kunitz and Max Hayward, includes all her landmark poems.

- Check Out The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova — This encyclopedic collection contains more than 800 poems and 100 photographs of Akhmatova.

- Explore Anna of All the Russias: A Life of Anna Akhmatova — This definitive biography paints a revelatory picture of Akhmatova’s life by drawing on a number of her memoirs, letters, journals, and interviews.

- The Muse of Keening — Watch this short film on the life of Akhmatova.

- About Anna Akhmatova — Read more about Akhmatova’s life and poetic works.