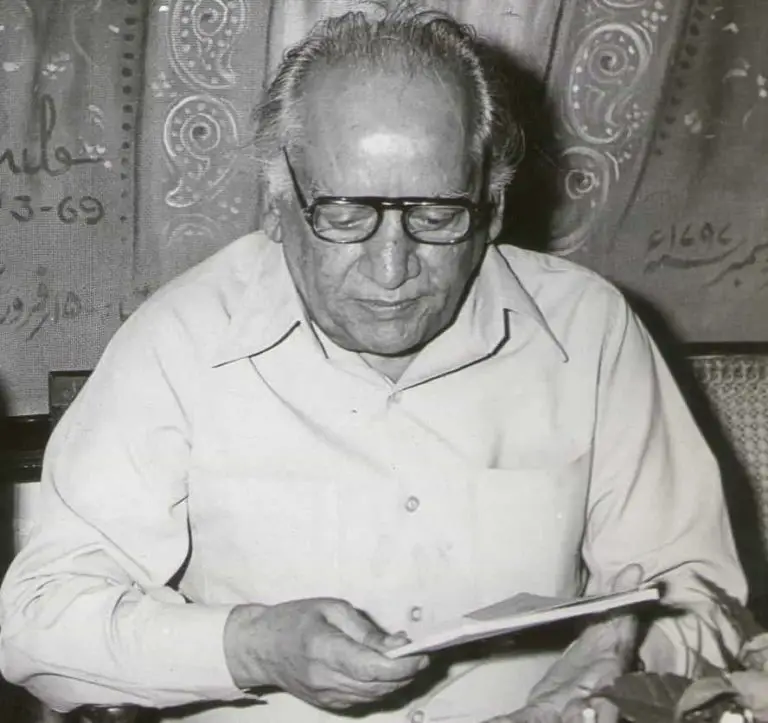

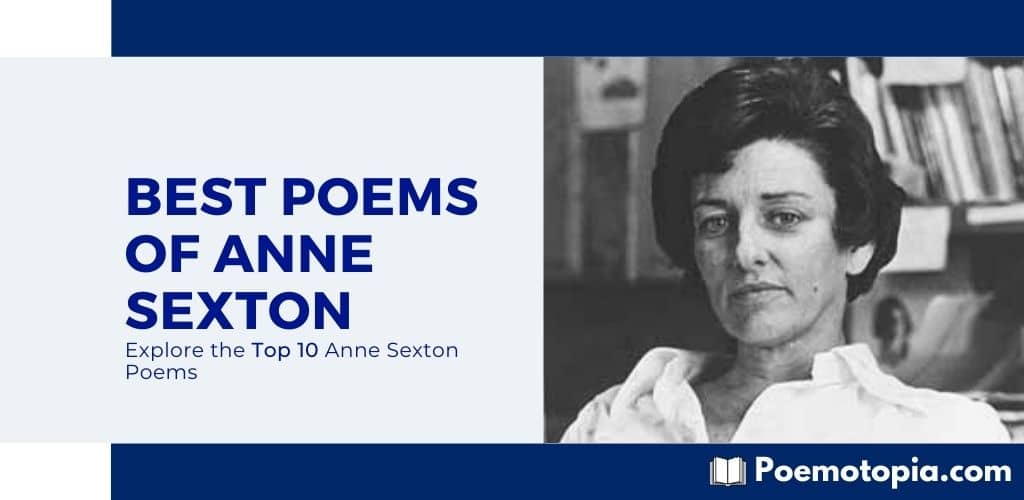

10 of the Best Anne Sexton Poems

Anne Sexton, one of the important 20th-century American poets, is famous for her confessional poetry. In her lifetime, she published a total of seven poetry collections. Three more collections of her poetry were published after her death by suicide in 1974. Her third collection Live or Die (1966) won the Pulitzer Prize in 1967. She also received several honors and awards, such as a fellowship from the Royal Society of Literature, the Shelley Memorial Prize, and a traveling fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Sexton’s poetry is marked by her personal emotions of grief, depression, and mental suffering. Poetry did not come to her as naturally as in the cases of other influential poets. It was suggested to her by her therapist, as a medium for sharing her intimate experiences. Throughout her life, she struggled with manic depression. In order to release her personal emotions, she chose poetry and mastered the art in a way that only a few poets could. In her review of Sexton’s final collection, The Death Notebooks (1974), critic Erica Jong wrote:

She is an important poet not only because of her courage in dealing with previously forbidden subjects, but because she can make language sing… When Anne Sexton is at the top of her form, she writes a poem which no one else could have written.

In this article, you can find some of the most famous poems of Anne Sexton that showcase her greatness and mastery as a confessional poet. These incredible poems unravel the unknown depths of Sexton’s mind.

Her Kind

“Her Kind” is one of the best-known poems of Anne Sexton, which was published in her first poetry collection, To Bedlam and Part Way Back (1960). This influential collection established her reputation as a confessional poet. Sexton said in an interview that she was warned not to be so expressive that she could trace her way back to objectivity afterward. Even her mentor warned her not to publish such a confessional piece like “Her Kind,” in which she boldly compares herself with a “witch,” a woman segregated from society:

I have gone out, a possessed witch,

haunting the black air, braver at night;

dreaming evil, I have done my hitch

over the plain houses, light by light:

lonely thing, twelve-fingered, out of mind.

A woman like that is not a woman, quite.

I have been her kind.

Throughout this free-verse piece, she uses the refrain, “I have been her kind,” to emphasize her stand. The following stanzas of the poem further develop on this theme:

I have found the warm caves in the woods,

filled them with skillets, carvings, shelves,

closets, silks, innumerable goods;

fixed the suppers for the worms and the elves:

whining, rearranging the disaligned.

A woman like that is misunderstood.

I have been her kind.

…

I have ridden in your cart, driver,

waved my nude arms at villages going by,

learning the last bright routes, survivor

where your flames still bite my thigh

and my ribs crack where your wheels wind.

A woman like that is not ashamed to die.

I have been her kind.

Listen to the poem in the poet’s own voice.

The Double Image

Sexton met the confessional poet William DeWitt Snodgrass, who would become her mentor, at a writer’s conference in 1957. Snodgrass encouraged her to continue with her unique poetic style. The titular poem of his first collection, Heart’s Needle (1959), influenced Sexton to write the heart-touching poem entitled “The Double Image.”

In “Heart’s Needle,” Snodgrass, by employing the confessional style, explores the pangs of separation with his daughter after his divorce. Sexton felt the same pain while she was separated from her three-year-old daughter Joyce due to her mental illness.

This long piece consists of a total of seven sections. Listen to the poem, with a short introduction by Sexton:

Read some of the memorable lines of the poem below:

I am thirty this November.

You are still small, in your fourth year.

We stand watching the yellow leaves go queer,

flapping in the winter rain,

falling flat and washed. And I remember

mostly the three autumns you did not live here.

They said I’d never get you back again.

I tell you what you’ll never really know:

all the medical hypothesis

that explained my brain will never be as true as these

struck leaves letting go.

…

I remember we named you Joyce

so we could call you Joy.

You came like an awkward guest

that first time, all wrapped and moist

and strange at my heavy breast.

I needed you. I didn’t want a boy,

only a girl, a small milky mouse

of a girl, already loved, already loud in the house

of herself. We named you Joy.

I, who was never quite sure

about being a girl, needed another

life, another image to remind me.

And this was my worst guilt; you could not cure

nor soothe it. I made you to find me.

Wanting to Die

One of the best-known confessional poems of Anne Sexton, “Wanting to Die,” should be read in order to understand what “confessionalism” really means. From the title itself, we can sense this poem is related to a speaker’s failure in coming to terms with life. Hence, all she wants is to die.

Sexton sent this poem in a letter to her friend Anne Wilder in 1964. It was later published in her Pulitzer Prize-winning collection, Live or Die (1966). Consisting of eleven tercets, “Wanting to Die,” has no set rhyming or meter. Through this poem, Sexton’s poetic voice expresses how her spirit longs for release from her bodily cage.

Watch Sexton reading the poem and explore some of its most iconic lines quoted below:

Even then I have nothing against life.

I know well the grass blades you mention,

the furniture you have placed under the sun.

…

But suicides have a special language.

Like carpenters they want to know which tools.

They never ask why build.

…

I did not think of my body at needle point.

Even the cornea and the leftover urine were gone.

Suicides have already betrayed the body.

…

Still-born, they don’t always die,

but dazzled, they can’t forget a drug so sweet

that even children would look on and smile.

…

To thrust all that life under your tongue!—

that, all by itself, becomes a passion.

Death’s a sad bone; bruised, you’d say,

…

and yet she waits for me, year after year,

to so delicately undo an old wound,

to empty my breath from its bad prison.

All My Pretty Ones

The titular poem of her second book of poetry, All My Pretty Ones (1962), is another best-known poem of Sexton. This poem is about a daughter who forgives her dead father for the pain he caused. While going through some old photographs, some faded memories emerge in her mind:

But the eyes, as thick as wood in this album,

hold me. I stop here, where a small boy

waits in a ruffled dress for someone to come …

for this soldier who holds his bugle like a toy

or for this velvet lady who cannot smile.

Is this your father’s father, this commodore

in a mailman suit? My father, time meanwhile

has made it unimportant who you are looking for.

I’ll never know what these faces are all about.

I lock them into their book and throw them out.

…

I hold a five-year diary that my mother kept

for three years, telling all she does not say

of your alcoholic tendency. You overslept,

she writes. My God, father, each Christmas Day

with your blood, will I drink down your glass

of wine? The diary of your hurly-burly years

goes to my shelf to wait for my age to pass.

Only in this hoarded span will love persevere.

Whether you are pretty or not, I outlive you,

bend down my strange face to yours and forgive you.

Listen to the poet reading “All My Pretty Ones”:

Sylvia’s Death

Sylvia Plath, another influential American poet of the 20th-century, met Sexton at Boston University in 1958. They both attended poet Robert Lowell’s class and developed a strong friendship. Thus, Plath’s death had a lasting impression on Sexton’s mind. She told her therapist, “Sylvia Plath’s death disturbs me, makes me want it too.”

Sexton composed the elegy, “Sylvia’s Death,” just a few days after she died, in February 1963. It was included in her collection, Live or Die. The poem begins with an impassioned address to her deceased friend:

O Sylvia, Sylvia,

with a dead box of stones and spoons,

with two children, two meteors

wandering loose in a tiny playroom,

with your mouth into the sheet,

into the roofbeam, into the dumb prayer,

In the last few lines, the poet describes how her death is nothing but an “old belonging”:

And now, Sylvia,

you again

with death again,

that ride home

with our boy.)

And I say only

with my arms stretched out into that stone place,

what is your death

but an old belonging,

a mole that fell out

of one of your poems?

(O friend,

while the moon’s bad,

and the king’s gone,

and the queen’s at her wit’s end

the bar fly ought to sing!)

O tiny mother,

you too!

O funny duchess!

O blonde thing!

The Truth the Dead Know

Here’s another piece from Sexton’s All My Pretty Ones. “The Truth the Dead Know” is an elegiac poem dedicated to her parents who died in the year 1959. Regarded as one of her best-loved poems, this short piece consists of four quatrains with the ABAB rhyme scheme. The regularity in rhythm alleviates the graveness of death. This piece highlights the themes of life’s futility and frustration.

Listen to Sexton reading the poem and read the full text below:

For my mother, born March 1902, died March 1959

and my father, born February 1900, died June 1959

…

Gone, I say and walk from church,

refusing the stiff procession to the grave,

letting the dead ride alone in the hearse.

It is June. I am tired of being brave.

…

We drive to the Cape. I cultivate

myself where the sun gutters from the sky,

where the sea swings in like an iron gate

and we touch. In another country people die.

…

My darling, the wind falls in like stones

from the whitehearted water and when we touch

we enter touch entirely. No one’s alone.

Men kill for this, or for as much.

…

And what of the dead? They lie without shoes

in their stone boats. They are more like stone

than the sea would be if it stopped. They refuse

to be blessed, throat, eye and knucklebone.

After Auschwitz

Written in 1973 and published in her final collection, The Death Notebooks, in 1974, “After Auschwitz” is a reactionary piece against the Nazi atrocities at Auschwitz, an infamous concentration camp during World War II. At the beginning of the poem, the speaker vividly describes one of the manifold horrific events that took place in the camps of Auschwitz:

Anger,

as black as a hook,

overtakes me.

Each day,

each Nazi

took, at 8:00 A.M., a baby

and sauteed him for breakfast

in his frying pan.

What was “death” doing when such things happened? According to Sexton, he casually looked at the events and picked at the dirt under his fingernail. In the rest of the poem, she takes a pessimistic stand against humanity:

Man is evil,

I say aloud.

Man is a flower

that should be burnt,

I say aloud.

Man

is a bird full of mud,

I say aloud.

…

And death looks on with a casual eye

and scratches his anus.

…

Man with his small pink toes,

with his miraculous fingers

is not a temple

but an outhouse,

I say aloud.

Let man never again raise his teacup.

Let man never again write a book.

Let man never again put on his shoe.

Let man never again raise his eyes,

on a soft July night.

Never. Never. Never. Never. Never.

I say those things aloud.

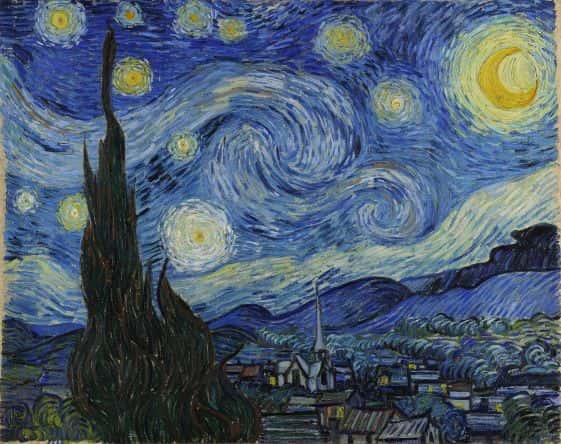

The Starry Night

One of the best poems of Sexton, “The Starry Night” is an ekphrasis of Vincent van Gogh’s painting by the same name. This poem was first published in her collection, All My Pretty Ones. Through this confessional piece, Sexton expresses her suicidal thoughts while meditating upon van Gogh’s painting:

The town does not exist

except where one black-haired tree slips

up like a drowned woman into the hot sky.

The town is silent. The night boils with eleven stars.

Oh starry starry night! This is how

I want to die.

…

It moves. They are all alive.

Even the moon bulges in its orange irons

to push children, like a god, from its eye.

The old unseen serpent swallows up the stars.

Oh starry starry night! This is how

I want to die:

…

into that rushing beast of the night,

sucked up by that great dragon, to split

from my life with no flag,

no belly,

no cry.

Listen to Anne Sexton reading the poem:

Cinderella

A feminist retelling of the story of Cinderella from Grimm’s Fairy Tales, this poem was published in her book of poetry, Transformations (1971), slightly different than her previous, overtly “confessional” collections. This long poem comprising ten stanzas explores the character and story of Cinderella in a new light. Explore Sexton’s take on “that story” you always read about:

Once

the wife of a rich man was on her deathbed

and she said to her daughter Cinderella:

Be devout. Be good. Then I will smile

down from heaven in the seam of a cloud.

The man took another wife who had

two daughters, pretty enough

but with hearts like blackjacks.

Cinderella was their maid.

She slept on the sooty hearth each night

and walked around looking like Al Jolson.

Her father brought presents home from town,

jewels and gowns for the other women

but the twig of a tree for Cinderella.

She planted that twig on her mother’s grave

and it grew to a tree where a white dove sat.

Whenever she wished for anything the dove

would drop it like an egg upon the ground.

The bird is important, my dears, so heed him.

…

Next came the ball, as you all know.

It was a marriage market.

The prince was looking for a wife.

All but Cinderella were preparing

and gussying up for the event.

Cinderella begged to go too.

Her stepmother threw a dish of lentils

into the cinders and said: Pick them

up in an hour and you shall go.

The white dove brought all his friends;

all the warm wings of the fatherland came,

and picked up the lentils in a jiffy.

No, Cinderella, said the stepmother,

you have no clothes and cannot dance.

That’s the way with stepmothers.

…

At the wedding ceremony

the two sisters came to curry favor

and the white dove pecked their eyes out.

Two hollow spots were left

like soup spoons.

…

Cinderella and the prince

lived, they say, happily ever after,

like two dolls in a museum case

never bothered by diapers or dust,

never arguing over the timing of an egg,

never telling the same story twice,

never getting a middle-aged spread,

their darling smiles pasted on for eternity.

Regular Bobbsey Twins.

That story.

Menstruation at Forty

Here’s another poem on our list of best Anne Sexton poems from her collection, Live or Die. In its review, poet and critic Louis Simpson describes the poem “Menstruation at Forty” as “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” This piece explores the themes of female sexuality, death, and patriarchy. Read how Sexton strikingly begins the poem:

I was thinking of a son.

The womb is not a clock

nor a bell tolling,

but in the eleventh month of its life

I feel the November

of the body as well as of the calendar.

In two days it will be my birthday

and as always the earth is done with its harvest.

This time I hunt for death,

the night I lean toward,

the night I want.

Well then—

speak of it!

It was in the womb all along.

The following lines of the poem reveal the speaker’s obsession with death:

My death from the wrists,

two name tags,

blood worn like a corsage

to bloom

one on the left and one on the right—

It’s a warm room,

the place of the blood.

Leave the door open on its hinges!

…

Two days for your death

and two days until mine.

…

Love! That red disease—

year after year, David, you would make me wild!

David! Susan! David! David!

full and disheveled, hissing into the night,

never growing old,

waiting always for you on the porch …

year after year,

my carrot, my cabbage,

I would have possessed you before all women,

calling your name,

calling you mine.

FAQs

One of the most famous and important poems of Anne Sexton is “Her Kind,” published in her debut collection, To Bedlam and Part Way Back (1960). This poem launched her career as a confessional poet. In this piece, Sexton describes a witch she strongly relates herself to.

Anne Sexton is best known for her confessional style of poetry. Her poetry is marked by their raw emotions, directness, and cleverness. Through her poems, Sexton explores several intimate themes, such as depression, death, and mental suffering.

Sexton struggled for the most part of her life with manic depression or bipolar disorder. It was her doctor, Martin Orne, who suggested that she should start writing poems in order to release her experiences and thoughts. Later Sexton attended Rober Lowell’s poetry class at Boston University in 1958 and became a published “confessional” poet in 1960.

Some of Sexton’s incredible confessional poems are “Her Kind,” “The Starry Night,” “Wanting to Die,” “The Double Image,” etc.

Useful Resources

- Check Out The Complete Poems: Anne Sexton — This is a must-have collection for the lovers of Anne Sexton’s poetry. It includes all the poems from her ten volumes of poetry, along with some unpublished poems she wrote in her last years.

- Check Out Anne Sexton: A Biography — This influential biography of Anne Sexton was nominated for the National Book Award and provoked controversy for its use of Sexton’s psychiatry sessions tapes.

- Explore Searching for Mercy Street: My Journey Back to My Mother, Anne Sexton — In this memoir written by poet Anne Sexton’s daughter, Linda Gray Sexton, she talks about her difficult relationship with her mother.

- An Interview with Anne Sexton — In this 1973 interview, she talks about “confession” and the “confessional” mode of poetry.

- About Anne Sexton — Read more about the poet and her works.